The Purpose Of A System Is What It Does

(Originally A Submission For The Catholic Worker Newspaper)

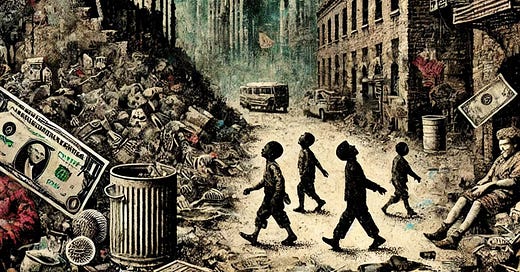

Meme’d into cliche only a few months after I first heard the phrase- “The Purpose Of A System Is What It Does”, POSIWID, originally a systems theory term which just meant “if it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck [...]”, is still probably the best way that I can explain why it’s so infuriating to see metal bars installed in the middle of public benches. Spikes on fire hydrants. Water fountains and bathrooms in nearly every park that I’ve been to in the last few years shut down with no apparent plans to be fixed. A million tiny signs that the city, generally, is not geared towards the needs of its inhabitants.

There seems to be a common assumption among many people that there are certain obviously undesirable chunks of the population who aren’t really meant to partake in public life in the same way that the average person does. Just a baseline truth. In itself not so much up for debate as where the line “undesirable” gets drawn. The visibly mentally disturbed homeless are obviously the most egregious offenders- plaguing parks and subways, mumbling to themselves, and so on. You can ask Daniel Penny- currently awaiting trial for the murder of thirty year old Jordan Neely, a homeless and mentally handicapped street performer who was held down and strangled on the F Train just last year while a crowd of people watched. After them, there’s the non-rowdy but still obviously homeless folks sleeping on cardboard beds performing their necessaries in bushes and allies, living it up, supposedly. Somewhere after that there’s the non-homeless mentally disabled, teenagers, smokers, anyone with an annoying little dog, tourists, buskers, street vendors, skateboarders, guys with speakers, and, come to think of it, anybody under a certain tax bracket.

There are solutions available regarding these problem demographics. To not have one’s view of the park besmirched by the odd homeless guy sleeping on a bench, we’ll install rails in the middle so that nobody can take up more than one seat at a time. Got some unruly looking ruffian taking shelter from the rain under your restaurant’s awning? Well what can you do but install metal spikes on the sidewalk, like you were building a moat for a castle? Some stores, creatively, have even begun emitting high frequency soundwaves from little speakers installed above their doors outside so that nobody can hang around for more than a minute without getting a headache. Why not turn main street into a warzone? Because that’s what it is- a subtle war between those who have no choice but to spend most of their lives in public spaces, and those who consider those other people eyesores. On the one hand, survival- On the other, aesthetics.

The most insidious part of this thinking, other than reducing others’ existence to objects in the environment that you can either pity, fear, or comfortably ignore, is how obvious, how clear-cut it’s made to sound, when those who hold these beliefs choose to take a stand about it. There is a matter-of-factness at play in how we speak about certain policies that we used to at least have the decency to make excuses for- having a healthier sense of guilt about these things even just a few years ago. Enough so that when the “Camden Bench” was first introduced in London in 2012, its sloped surfaces and overall intentionally-uncomfortable design were posited by Factory Furniture, fabricators hired by Camden Council, as simply a means of “minimis[ing] the amount of time people spend in an area. With a perched or sloped surface, people can't loiter for too long.” Loitering, of course, is a gloss. It conjures more the image of a teenage ne’er-do-well, free of class and racial associations, an easy boogeyman to sell an atomized public who hates, more than anything, to have to interact with other members of the public. The nonspecific “loiterer” is much easier to disregard and exclude than the all too specific, all too real homeless population who sit on your benches, yes, even drink from your water fountains, who are the real targets of this kind of urban design. In February 2021, after an unannounced mass removal of benches from NYC’s subway stations, the official MTA twitter account stated directly that it was in an effort to keep homeless people from sleeping on their premises. Played nonchalantly. As though even if that were a good enough reason for the removals, that the obvious ramifications for the disabled, elderly, pregnant, and anyone who’s just plain tired, aren’t even worth mentioning. There was a public outcry, of course, and within a few days the benches were brought back.

This may seem a small issue to some but there are layers of meaning, social engineering really, regarding something as simple as the design of a public bench. Or its absence. Or the decision to leave a public water fountain permanently defunct. Or NYC’s decision to close all the libraries on Sundays. Or a million other city and property management-made issues that don’t seem to do anything but make life harder for the most already-vulnerable demographics, and make the outside world/public spaces just plain uninviting for everyone else.

If the issue of hostile architecture were relegated to just how uncomfortable benches and bus stops have gotten then it’d be bad enough. But it is, like all matters of public policy, a symptom of something bigger and weirder in the American psyche. A chilling toleration for collective punishment that says “I don’t care if an old woman walking around the city all day has nowhere to sit, I don’t care if a student putting in overtime at the library has no available bathroom, I don’t care if there’s simply nowhere to just be without having to spend any money. As long as the homeless are kept away from me, as I long as I don’t have to think about them, I’m alright.” And of course, this might even be the tiniest bit justifiable if the idea was to direct the homeless away from unstable makeshift living situations and towards somewhere where they can get the help they need1- but this assumes some imaginary neighborhood, somewhere out there, that’s more welcoming to these “problem demographics” than the average New York City park or bus stop. A magical somewhere-else-land, the type that gets talked about all the time on the news, that offers indefinite rent-free housing and immediate job placement. But there is no such place. When the homeless are driven from public life, there is no flying south for the winter. Often, they just die. This is, of course, still the generous reading of pro-hostile architecture sentiment- given that a 2023 poll by The Research Co. found that about ⅓ of Canadians were in favor of simply euthanizing their homeless populations.

Well anyway, subway suicides are on the rise again. The first few months of 2022 saw a 50% increase of in NYC. Other studies have shown that 35.85% of homeless suicides occur in “Transport Areas” such as highways or subways as opposed to only 8.56% percent of non-homeless suicides (NHCHC 2018), and that recent rises, while certainly attributable to a million factors that govern the overall quality of life for the average homeless New Yorker, can almost certainly be seen as the outcome of a city that’s grown increasingly infrastructurally hostile to them. And if I know this, then the MTA knows it. And if the MTA knows it, then they should do something about it. And if the MTA doesn’t do anything about it (besides a few cheap posters hung on the ends of subway platforms now, reminding would-be suicides, emptily, that there are those out there who care about them) then we can assume that a suicide epidemic among the homeless is an acceptable outcome for them. Because I see no reason to give them the benefit of the doubt, it has to be said- The Purpose Of A System Is What It Does, and what hostile architecture does is kill people.

A brief aside- it’s interesting how often greater public accessibility is mocked for serving the “lower” or baser needs of the public. Lactation rooms, bathrooms, somewhere to sleep, all considered oddly unnecessary, or somehow conducive to other more illicit behavior should those most immediate needs be satisfied. When I used to help Kansas City’s Food Not Bombs, there was always the occasional side-glance from some pedestrians at the row of free condoms made available on the table next to the soups and sandwiches, to which I think it needs to be asked- is sex a privilege? Something, like homeownership or having kids, meant to be put off until you’re in a more stable or “responsible” place in life?

You’d be surprised at how many people think so. Not just from the usual Pleasantville-style Republican quarters either. There’s a sort of liberal squeamishness about needing to make public spaces congruent with our bodily necessaries that makes you wonder, even, if we’re supposed to transcend needing to shit or sleep or breastfeed by virtue of being polite, civic-minded city folk. The earliest recorded pieces of hostile architecture were “urine deflectors”- cement installations in certain street corners in nineteenth century London, constructed at certain angles meant to redirect a stream of urine onto the offending pisser should one try to relieve themselves where one is not wanted. Its modern equivalent- a hydrophobic paint applied to the fronts of buildings in Germany to achieve the same wet reprisal, is indicative still of a certain need to punish those who are unfortunate enough to be in the city and inhabiting a human body. Why this money can’t be more constructively spent on opening a few more all-hours public bathrooms and a few more janitors to maintain them is beyond me. Certainly it would be more direct and effective than the kind of pisser’s arms race that exists right now between city and citizen- because it’s strange that not only are these fixtures designed to discourage public urination, but to punish you, in turn, with your own urine. It’s funny enough of an image that it almost makes you forget that we’ve turned our street corners, literally the corners of buildings themselves, into judge, jury, and executioner. Maybe next year we can look forward to street lamps that give you an electric shock when you try to lean on them, or sidewalks that burn your feet if you stand in one place for too long. You tell me if that’s any more ridiculous than a wall that pisses back on you.

All of this is to say that somewhere along the line we’ve become too comfortable with the idea of public infrastructure run like private companies, and private companies run like fortresses. We need to question the assumptions that lead to such bizarre beliefs, dearly held by so many, as “Why should the homeless be allowed to sleep in parks?” or “Why shouldn’t the library eject people who just need somewhere to rest?”. As long as it’s considered normal to prioritize the abstract “cleanliness”, or image, or profits (that we don’t share in) of institutions that, nominally, are meant to benefit everyone (even those whose life circumstances place them in “eyesore” territory), we will never be more than a society of angry customers, a bunch of loudmouths. People so addicted to convenience that, with the whole world “looking out for us”, there’s nowhere to just be but our own tiny little apartments. No one’s company to enjoy but our own. The only pleasures being those we can afford, and which only really please us so long as we can pretend that they were meant, all along, only for us.

Factory Furniture even said in an interview with Unpleasant Design- “Homelessness should never be tolerated in any society and if we start designing in to accommodate homeless[ness] then we have totally failed as a society. [...] perhaps it is good that we feel that and recognise homelessness as a problem rather than design to accommodate it.” A weird little bit of word hucksterism on their part that seems to sympathize with the homeless while actively making their lives worse.